Mario Dellavedova, Jimmie Durham, Tim Hawkinson, Ilya Kabakov, Jannis Kounellis, Mike Nelson, Luigi Ontani, Tom Sachs, Samuel Porritt, Daniel Silver

Heads

28th September - 11 th November 2006

SPROVIERI

27 Heddon Street London W1B 4BJ

In the Capitoline Museum in Rome there are several busts of Socrates. The myth has persisted that Socrates’ appearance derived from the labour of his mind. The likenesses of him suggest that his brain grew like a muscle through a process of continuous breakage and healing resulting in a cranium that bears down heavily on his brow. This notion, that the outside of the head betrays its inner workings, might in part be dispelled by the story of Erasmus who famously possessed an exceptionally small head. So much so, that he wore a specially constructed wig and biretta to disguise it. Unlike the majority of busts that survive their subjects, the sculptures of Socrates still perform the purpose for which they were made, in that they maintain his memory. Heads passed down to us bereft of their subjects’ names and biographies have attained a different status, and are open to any number of readings.

Much of the work in the exhibition has taken the purposelessness of making a portrait today as its point of departure. In dispensing with the history of the subject, the head assumes a peculiar versatility. As with the face, we are destined to see the likeness of a head in even the most misshapen of naturally occurring things. We can stretch our powers of recognition to see a head in nearly anything roughly spherical that possesses disproportionate information on one side. Several pieces touch on this. In one instance the shape of a small figure slumped over a barrier gestures at the nose of a face. Another work suggests an animal head made from a baseball cap, folded in such a way as to indicate eyes and a snout.

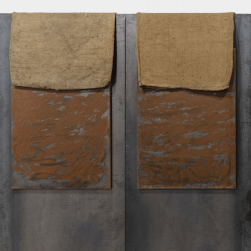

It could be claimed that the face naturally lends itself to painting. Like paint, the face is changeable and responsive. In contrast to the mobility of the face, the head as a whole may be considered lumpish and static, and this is something that a number of the pieces play on.

Certain other works in the exhibition may be viewed broadly as self-portraits, the absence of a single external subject providing a space filled by what the artist’s own head contains, the sum of all heads, and as such a particular view of humanity.

In the context of the exhibition the inclusion of a skull not only leads us to thoughts of mortality, but also causes us to think about the skull as an armature. In this light it can be considered a democratic object, something we have in common once stripped of the flesh, hair and tissue that makes us visually distinct.

Text by Samuel Porritt