Jannis Kounellis, Giorgio Morandi

31st May – 4th August 2001

SPROVIERI

27 Heddon Street London W1B 4BJ

The Classical Timelessness of the Avant-garde

text by Achille Bonito Oliva

'Modernity, the transitory, the fugitive, the contingent, the goal of art, for which the other half is the eternal and the immutable: there exists a modernity for each antique painter' (Charles Baudelaire). Baudelaire's declaration could well be ascribed to this exhibition: a juxtaposition of the work of two Italian artists, Giorgio Morandi and Jannis Kounellis, whose work, one might imagine to be separated by a gulf in terms of generation

and apparent poetics.

The poetics of Morandi is founded in the metaphysical capacity of art, and specifically of painting: to explore the nature of things, to represent both their fleetingness and durability. And yet a similar aspect is pursued in the installations of Kounellis, which aim to capture the interweaving of space and time.

Both artists, with absolute coherence, with the Zeitgeist of the twentieth century, pursue a poetic constantly updated by a formal and constructive anxiety, one that is of a linguistic order referring to another, superior and ethical order which finds its roots in Leonardo da Vinci's insistence that 'painting is a conceptual thing.' The conceptual attitude of the work of art, even if it is realised with material outside the pictorial, is based in the historical awareness of the two artists who, by searching in the transitory and fugitive, tease

out a classical and timeless essence.

Morandi and Kounellis find in form the ground for an elaboration of work which continuously refers to historical space and therefore to memory. If art transforms matter, it does so in the security of a spatial

frame with the interaction of a temporality which founds, in Morandi's work, a precision through representation, and in Kounellis's through processuality.

In any case, both artists are the product of the great Western tradition of an art founded in techne’, the metamorphosis of matter and symbolic condensation into a form responsible to its own linguistic order. This order is a product of a process of formalising the image, one that shifts the initial turbulence of the creative

process towards the tranquillity of an objective and transparent vision.

Morandi and Kounellis are avant-garde artists in the sense of their artistic praxis as continuous experimentation. Each work is a product of an intense and specific elaboration and yet, at the same time, in

its formation, effortlessly arrives at a classical timelessness of form.

Both artists share and are the product of a culture which finds its model in the classicism of the Greek world and in its renewal through the passion of the Italian Quattrocento. Geometric perspective is not only the symbolic form of an anthropocentric ideology, but also a vision of the world that refuses to add order to order, but rather to reconcile external disorder with stoic nostalgia for the aura of control.

The auratic moment of this attempt at reconciliation represents exactly the symbolic side of art, the Platonic movement of the encounter between artist and history, the circuit between the Dionysian aspect of the former

and the Apollinian gaze of the latter.

Morandi and Kounellis understand how to find an equilibrium between the experimental anxiety of the avant-garde and a classical resolution. Both believe in an idea of art as visual thought, an iconography of the landscape of the soul inhabited by the monocular gaze of the artist.

Morandi develops his own personal poetic of the metaphysical that does not search through the perspective order to mock the world, as does de Chirico, but rather, he reduces his play with the world to the installation of an internal space inhabited by the inanimate presence of still life.

If, from Leonardo he adopted the conceptualisation of pictorial method, the subtle and silent passion of Michelangelo also constantly accompanies his work. 'L'a togliere' of the great artists of the Renaissance - the revelation of an inherent form or image in the material -becomes, in Morandi as an artist of the 20th century, 'lo spegnere' - the dematerialisation of form. The painting loses chromatic emphasis and follows a kind of entropic destiny that leads to monochromatism and a dimming of light. A pre-Minimalist rigour inhabits Morandi's still lives; a hero of a private interiority, he develops an iconography that reflects upon the transitoriness of time and transforms the genre of natura morta to natura morte - death in nature to nature as death. All his paintings possess an iconographic cadence - cultural and philosophical parallels with artists and writers, such as Giacometti, Beckett and Bacon who may seem distant from him, but whom, in my opinion, intersect with his work, Nonetheless, in relation to these authors Morandi maintains a febrile perseverance of making and thematic consistency. In his work there is, at first glance, a laborious handiwork that seems to reduce the conceptual aura of the work compared to that of these other authors, who make of silence, decay and the scream a constant cipher of their own poetic.

But the outline of the figure of Giacometti finds in Morandi's object a correspondence of vision and linguistic structure. So also the extinguishing of Morandi's composition seems to allude to the space of a Beckettian conversation piece, without jump-starting, without abrupt changes of chromatic temperature: an iconographic monologue against the two interweaving monologues of Beckett's theatre.

It is, in any case, the perspective, the spatial grid, that defines the parameters of Morandi's image, that requires a minimal composition, in contradistinction to Bacon's image, which unable to reconcile itself with perspective, uses a photographic and pictorial memory, a Titian-like nostalgia for perspectival order.

Morandi, in his use of the expressive plurality of the 20th century, seems to introject 'spegnere' - the entropic dematerialisation of the world that still yet offers us its iconographic banquet. The artist doesn't ask that you find it palatable but rather that you contemplate the definitive state of things. This attitude requires a gaze that is profoundly exemplary and classical, a vision of the world that we also find in the work of Kounellis. It is one that doesn't ask art practice to console us, but rather asks it to carry out an operation of continuous investigation and self-interrogate.

From this attitude, the Italian artist of Greek origin, rescues everyday objects and natural materials, reassembling them in a formal order that, drawing on the traditions of painting, preserves the necessity of form

as symmetry, proportion and harmony. This characteristic is the signature of Kounellis's work, one founded on the awareness of art as linguistic catastrophe, relying on a progressive process of deconstruction with a subsequent formal re-founding.

To the fugitiveness of Baudelaire Kounellis counterposes a possible classical timelessness of modernity. To the performative emotiveness of much contemporary art, including that of British art, Kounellis counterposes the durability of a gaze that witnesses and participates in the world, supported by a point of view that does not feed on the documents of the everyday like Pop Art, but rather nourishes itself on the constant breath of history.

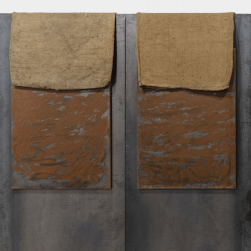

History for Kounellis, as for all European artists including Beuys, means memory, the possibilty of drawing on the eternal subject of classical painting from which to found new iconographic solutions capable of extending art beyond the limit of the canvas into the space as installation. In this way, the metal sheet as support becomes, for Kounellis, a harmonic surface upon which, in an extreme physicality, hangs the flesh of a cow. Still life here finds its representation by playing on the classic timelessness of form, which nonetheless draws vitality from the anti-classical quotation of nature - not represented but rather directly presented as material.

The work becomes a contest between space and time: with the clarity of an x-ray, the dialectic, always intrinsic to the history of art, is the decay of time, presented, but at the same time, rescued by the formal permanence of the work.

Here, space does not yet extinguish the beat of time. It constitutes the frame in which the decomposition of matter is recuperated in the unitary composition of the work. The iconography of Rembrandt's painting finds

a kind of didactic explication in that of Kounellis which, in relation to the earlier artist's trompe l'oeil, substitutes the density of matter's vivacity - including also its smell. Here also there reappears in the work the familiar tension of the avant-garde that strives to reduce its distance from things. Kounellis accompanies this distance with an awareness that only a new formal order can develop a renewed vision of beauty and a new process of knowledge.

Moreover, the work, through the strength of its conviction, never loses sight of a spatiality that incorporates, as did the architecture of ancient Greece, all the conditions of social communication. In a certain sense, Kounellis is like Hogarth or a kind of a Mondrian-of-the-ruin.

Ultimately, Morandi and Kounellis, in the distance that separates the historical from the neo-avant-garde, constitute two exemplary moments of Italian art whose search for beauty as a defence against the world

is nonetheless always resistant to the elegance of an easy solution.

Both artists carry a temporality of the 20th century threatened by the expropriative speed of technology and the telematic image. Both artists constitute a model of aesthetic production as ethical resistance, durability as against ephemerality, the capacity to temper the impatient experimentation of the historical avant-garde with formal solutions capable of addressing primary questions.